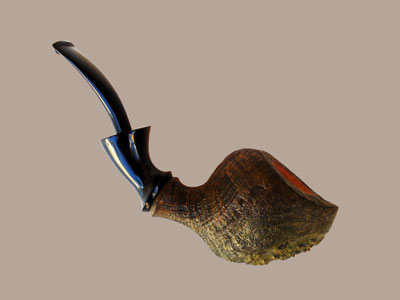

It is not often that I get excited about something, but about a week ago, that all changed. A friend gifted me a stummel that he had carved and then had the misfortune of cracking the shank. More out of curiosity and boredom, I decided to finish the pipe and proceeded by shortening the shank and fitting an army-mount Ebonite extension.

And then I lit it!

Now why, I hear you ask, was I so excited? Because, dear friends, the pipe is not briar, but Combretum imberbe, known in English as leadwood or in Afrikaans as hardekool (translated as “hard coal”). It is hard, very hard, dense and heavy. It is used as firewood, especially in the Bushveld, where it is widely distributed. Unlike briar (yes, read that again!) it burns very slowly and the early Boers kept a log smouldering all night to keep wild animals at bay.

I am not the first to use it for carving pipes, as that honour should go to another South African carver, Ebenhart Botha, who sometimes uses it in his “African wood series”. My apologies to him for doubting his word about the smoking qualities of these pipes. I doubted him because he also sometimes uses African blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon) about which he raves. But, after carving a few African blackwoods myself, gave it up, because I was, to say the least, less impressed and consequently thought that Ebenhart did not know what he was talking about.

OK then, if it is so great, what does it taste like? Well, frankly, it tastes like nothing, except perhaps for the tiniest hint of a campfire, late at night, under a dark African sky. I always thought that Mac Baren HH Old Dark Fired was my favourite tobacco, but now I know that it is. There is none of the tongue biting harshness one experiences when lighting up a briar for the first time. There is no need to suffer the agony of “breaking it in”. Here, finally, is a pipe to end the bowl-coating debate once and for all, for none is needed!

Another friend, when I was waxing lyrical about my hardekool pipe, remarked that it could not possibly be that good as the wood was not nearly as porous as briar. I retorted that I could for the life of me not see why it would be important for a pipe to be porous. What about the old clay cutties, or the Dutch porcelain pipes? Admittedly, these are not very good smokers, but then there are the Chinese Rhamnus pipes, just as dense and hard, and excellent smokers.

Who has not battled to exorcize some heavy aromatic ghost from a prized estate pipe? If you would rather have a sponge drenched in tobacco tars and nasty oils, then I suggest you stick to your briar. But, if you want a pipe that you can simply push a cleaner through, wipe the inside of the bowl with some tissue paper, stuff it full of tobacco, light up and sit back, relax and enjoy, then I suggest you try a hardekool pipe.

Unlike the man who claimed that he would rather fight than switch, I immediately set about carving myself another hardekool and lo and behold, the results were the same. I have not stopped smoking both of mine. There has hardly been a moment without one in my mouth. The only difficulty was deciding which one needed a break more. Not for a moment did either one ever complain or turn sour or nasty on me.

OK, there must be downsides, right? Of course there are. As with all good things, there always are.

As mentioned already, the wood is heavy. My second pipe (the top one in the photo above) was carved to be as near a copy of a briar pot (the bottom one in the photo above) as I could make it. The stummel of the briar pot, incidentally also quite a good smoker, weighs in at 35.9 gram and that of the hardekool at 51.7 gram. A difference of 15.8 gram. So perhaps if you like to clench your pipe, you should consult your dentist first as to whether your teeth would be able to handle it.

The grain of hardekool is not as fine as that of briar. It is coarser and thus it is somewhat difficult, if not impossible, to obtain the same smooth surface, but for my money, I would rather have a workhorse in my hand than a figurine of a pony sitting on a mantelpiece. I have never been one for a shiny bauble that, in the smoking department, fails to live up to its shiny promises. Somehow, the finish I was able to obtain, reminded me of my grandfather’s pipes that, after he died, lay forgotten in a drawer for years. The same caressed, well used and well-loved sheen.

All woods with grain running length-wise in one direction – and especially the harder, denser woods – are prone to cracking and splitting along the grain. Many is the time I have cracked the shank of a wild olive pipe when trying to force in a too tight tenon. Incidentally, this is something that is far less likely to occur with briar, because of the nature of its grain.

For this reason, I decided to employ a construction along the lines of the famous (or infamous) Keyser pipe, so well-known and loved (or hated) in South Africa. I used an aluminium extension with an army type push mount and, rather than Ebonite, chose a Lucite stem, all adding up to less maintenance and more smoking pleasure. I hate stain. I hate having to paint a piece of wood with artificial colours. With hardekool, not a drop is necessary. Why, you would even be able to clean your pipe with denatured alcohol, if you so choose, and it would have no ill effects.

Hardekool is far from easy to carve. Anyone who has ever said that briar is hard, does not know his chalk from his cheese.

Instead of calling the pipes “Bushveld” pipes, I could well have chosen to call them “huntsman” or “woodsman” pipes. As indestructible as is humanly possible to make them, humble and hardworking, these pipes could very well come in handy when out alone in the woods and there are wild animals to be kept at bay.

I honestly think, you owe it to yourself to try one. I have kept the prices reasonable, so you have no excuse not to try one.